For most teenagers, rock and roll rebellion was about being different. For me, it was about wanting to be the same. As a child I never stayed at the same school for long and was always outside the codes, dressed in the wrong uniform, without a gang, home alone.

At eighteen I came to London with a head full of punk rock and took a job washing up in a department store kitchen. I stayed in a hostel - ten to a room in bunk beds, peeling lino on the floor. It was December and the electric metre was greedy for coins to feed the bar fire. The idea was to find like-souls at gigs, form my own gang, wreak revenge, reach for triumph and celebrate victory by June. But it was four and a half years before I took an acting job and met Torquil Macleod when the angels for whom I had been searching began to gather about me.

|

But during those years I caught glimpses of them - a glittering wing tip while hearing certain songs on John Peel or a wisp of holy silver hair while witnessing something wonderful, standing alone at the back of the Electric Ballroom. Time was spent swerving between the dole and crap jobs; selling shoe cleaning sponges in Woolworths on Oxford Street and working as a nightclub hostess off Piccadilly, where I would drink watered down wine, dance with fat businessmen and light their fags while their eyes rolled from the whiskey and their thighs sweated at the promise of young female flesh. I lived in a succession of terrible rooms, where beetles crept up between the bare floorboards; small creatures in April that grew fat and crunchy underfoot by August, and where you had to side-step pools of piss to get into the bath. One stretch of homelessness I had a key to a student hall of residence and sneaked into the television room some time after midnight when the programmes had finished, putting chairs together to sleep on, and sneaking out before the cleaner came around at six the next morning. I dreamed of railways and owning a car - towards, towards, towards something better. French scent, silk underwear, hairdos like Dietrich, electric guitars. A kitchen, a bathroom, a sofa to sit on.

|

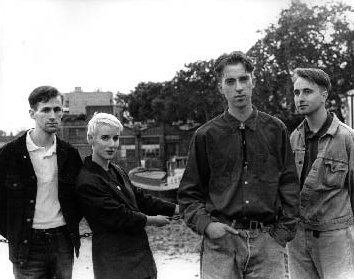

Members

Andrew Brown, bass |

Evicted from my bedsit in Colville Terrace, I moved into a squat in Bermondsey, near Torquil's squat in the Walworth Road. We shared the same dreams and looked for the same stars and cursed the same devils and I no longer had to go to gigs alone. He had a primitive drum machine and helped me to record my songs onto his reel to reel, playing bass and working knobs and switches to give form to spirits.

Evicted again we crossed back over the river. Words and tunes kept appearing and were written in small hardback notebooks, carried everywhere. We ran around town - Chalk Farm, Brixton, Kentish Town, Ladbroke Grove - all played host to an uprising of heroic, unique, dangerous and heart-filling groups that lived outside the expected. And now I had tapes in my pocket to lure same sensibility souls to my cause. I didn't own many clothes, but style was all - my one good shirt went to the dry cleaners every week. Chipped red nails varnish at all times. (Un-chipped would have displayed the aspirations of a secretary.) Skins, the sea, railways, towards, towards … every four weeks to the Great Gear Market in the Kings Road for a dyed blonde hairdo - a week and a half's dole money - but savings were made on food, living off Tesco porridge at 37p 1lb and apples from the stall in Churton Place.

|

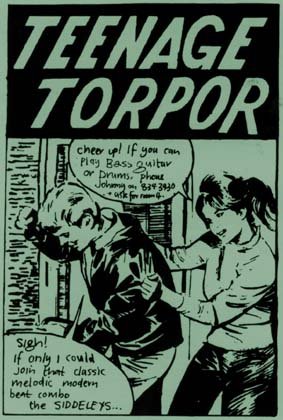

Allan Kingdom was a regular at the Bay 63 in Ladbroke Grove. He paid attention to sartorial matters, visited the barber once a fortnight, sneered at the ridiculous and played a guitar. He took my tape and learnt the songs. Once I had Allan in my gang we began to run faster. With a loathing of the limitation and corporate nature of adverts in the NME and Melody Maker, we put up small posters informing potential bass players and drummers of our loves and intent. Brown ale by the Scrubs, the June Brides, Raymonde, certain hairdos. We put the flyers in the places where future Siddeleys would spend their time - The Rough Trade Shop and around the walls of the Bay 63 and other gig venues, where we would post our bills within minutes of arriving.

A series of coincidences and inevitabilities led to the materialisation of Andrew Brown at a Charing Cross Road nightclub. He shared our love of northern soul, punk rock and underground independent classics. He also shared hairdresser and tailoring requirements; an Essex-boy genius. No stranger to the Triumph motor car and motorcycle brands that we held in our hearts, he was a very funky dancer. And he had a friend called Phil who played drums.

It was time to get to work and do what mattered. The Siddeleys' first gig was on 1st December 1986 in the basement of The Clarendon Ballroom, before the blanding of Hammersmith Broadway. It was a new moon that night, but Phil's drums were locked in some studio, and the key was missing, so he had to stand up and whack a solitary floor tom and we lost not only our rhythm, but the thing that set us apart for that night. Still, The Legend wiggled in the auditorium and said we had potential.

The second show, on 21st January at Westfield College was much better, and then suddenly there were fans. Letters arrived, fanzine articles appeared. Mysterious and inevitable, but we always suspected we weren't alone. The future never looked so bright. The Siddeleys opened up a world to me that I'd always known was there by couldn't get to. Suddenly the door was open and there were days and nights of talking to people who not only understood the idiom, but could speak it, too - I was 100% me, 100% home. The afterglow of punk rock was all about us and there was this magnificent outsiders' gang.

|

Allan's bit

When I met Johnny Johnson in the spring of 1986 I was living in Didcot, Oxfordshire with my parents and younger brother and sister. I'd played in schoolboy bands in friend's bedroom and loved playing the guitar. Didcot was a boring place to grow up in, but London was less than an hour away on the train. I spent most of my spare time practicing the guitar and spent most weekends in London seeing exciting new bands. My friends and I had discovered a semi-underground scene where bands would play in rooms atop pubs, in deserted Ambulance stations and at Bay 63 in Ladbroke Grove. I liked the Pastels, the Shop Assistants, the Bodines and 1000 Violins. I had seen the early shows by the Jesus and Mary Chain and Primal Scream who, at that time, were a great band. My favourite groups of the early 80s had either split up or were verging on self-parody. I was young, single, bored and was open for new experiences. I'd dreamed of pop stardom, of Fender electric guitars and of leaving my small town life... I am proud of what we achieved, proud of the fact that the photographs of us have aged so well. We were not subject to the dictates of fashion, thank goodness, for the fashions of the late 80s were truly ghastly. We always stayed true to our vision - there are no "baggy" remixes of Sunshine Thuggery and no photographs of us with mullets of leather trousers. My only regret is that we were not given the opportunity to record the songs well. The sessions that we gratefully recorded for the John Peel show best reflect what we were capable of. Even those sessions were difficult, especially the second session, which was produced by Dale Griffin. "Buffin" was in a foul mood when we arrived at Wessex studios and took an instant dislike to me. He moaned about our equipment and behaved like a total tossser. Thankfully the session sounded great. |

Walking the streets I collected fire escapes, adding their locations to a piece of paper pinned to a notice board - Shillington Street, Fulham Road Police Station, Vauxhall Bridge Road. On hearing of this fine collection David Payne of Trout Fishing in Leytonstone agreed to us recording 'Wherever You Go' for a flexi for the next edition of his fanzine, 'Trout Fishing in Leytonstone', sharing the disc with Torquil's group, Reserve.

Around the same time, Andy Wake heard one of the demos I'd made with Torquil and signed us to Medium Cool on the spot. We recorded 'What Went Wrong This Time?' down by the river in Rotherhithe - a dilapidated 8-track studio in the shadow of the dead docks. Outside, people had used spray paint as fragile weapons against the encroaching developers, pleading for their homes to be left alone and for new buildings for the rich not to smother them. Spray paint, a fine weapon at times, proved inadequate defence there, and their slogans now lie buried beneath the stark, antiseptic new apartment blocks. We recorded the single in a day, despite the engineer disappearing for hours at a time, and did the final mix on his car radio, all piled into his Mark III Escort. We needed to hear what it would sound like on the nation's trannies.

We found a place to practice round the back of King's Cross station. Phil had to slip away, back to his jazz band, and Dean Leggitt showed up, clutching his snare and some sticks. Dean stayed a while and played some shows, and then left a week before our first UK tour.

In between, we walked along the Grand Union Canal, played the machines at Southend and dreamt of The Leather Boys and the romance of the North Circular Road. We went to gigs and drank brandy from secreted hip flasks. Coastal towns harvested fairgrounds with tattooed greasers who flung the waltzers around. The smell of fried onions and fags would twitch our senses all the way back to the Dive Bar in Gerrard Street.

|

The Peel Sessions:

Session (23.May.1989) |

David Clynch also arrived clutching a snare and some sticks, but stayed longer. We recorded Sunshine Thuggery in three days and even had a producer this time in John Parrish. 'Sunshine Thuggery' was released in August 1988 on David Payne's Sombrero label. John Peel was very taken with the EP's second song 'Are you still evil when you're sleeping?' and invited us to do a session. We watched our menial day jobs drift into the distance. If only.

By this time I was staying in a studio flat hard by Queens Park railway station. Letters of love and joy had started to come from people who had seen us or heard us, but someone was stealing the mail and lots of it never reached us. After a while, one of my neighbours went to jail, and more letters seemed to get through.

What next, what next? We were like dogs in traps, eager for the track. We toured a little, always in the middle of winter - more accident than design, but then we never were a summer sunshine act. Sitting in caffs behind the steamy windows of rain hammered glass - that's where the warmth is. Staring out and counting wishes - the gaps between the records and the gigs were angry crevasses for us - but they seemed surprisingly hard to navigate.

|

We recorded a second John Peel session and made plans to release 'You Get What You Deserve' as a third single - this time, this time - but nothing happened. Sombrero had no money left. Other record companies were interested - some large and some small, but they slipped and they slithered from grasp, as hard to hold as a fistful of mist. Nothing came to anything. I never could understand why; it didn't make sense. The live reviews were always good, but small. There was never any space to speak - just one or two misquotes that found their way into print. It was as if we were swimming against a tide that changed direction whenever we tried to swim for another shore. There was no way through, no matter how true our compass points were. Buffeted by impossible waves, we began to tire. The walls inverted and suddenly I was on the outside again, a refugee from the Tower of Babel as the people who shared our language faded away like ghosts.

What an irritating paradox. A real outsider will always remain outside, doomed by their very nature. After all, once they're on the inside, how can you ever be sure that they meant it, that they were what they appeared to be from the other side of the wall?

But there's no time to ponder this now. It's getting late, and I must go out, for there are still three hundred and twenty six fire escapes left to be accounted for in the London dusk

|

Andrew's bit

Where music is concerned, as long as there's a good tune then I'm interested, always have been. In that sense my taste hasn't really changed much over the years. From the Velvet Underground to Northern Soul you can count me in. …and of course, lest we forget, Elvis will never leave the building. |